By: Nick Haddad

Protecting Your Catch and Boosting Survival Rates

Two of the largest issues that both anglers and fisheries managers face today are catch and release mortality (often from barotrauma) and depredation from apex predators. Both of these topics are such pressing concerns because they lead to large sources of fishing mortality, without the angler getting to take home their catch. In an ideal world, the vast majority of fishing mortality would occur from harvested fish, not those that die after release or that were eaten by predators. While these issues are separate, they can be related when it comes to depredation or predation of released fish.

Understanding Depredation

Depredation, by definition, is the removal of a captured fish by a non-target species. In the vast majority of cases, depredation is referring to a fish that is hooked, then eaten while an angler is fighting it to the surface. The far less common use of the word “depredation” occurs when a fish is eaten off a fish descending device. This technically differs from the word predation, which would occur if you released a fish on the surface and it was eaten by a predator, which is a more common occurrence.

Common Predators in Depredation Events

The most common predators involved in depredation events for the Gulf offshore fishery are primarily a variety of shark species, dolphins, goliath grouper, or barracuda. Primary predators tend to vary geographically, as well. In Southwest Florida, goliath grouper depredation is a much larger problem than other areas, while dolphins tend to be more of an issue on the Northern Gulf coast. Some anglers also consider large amberjack a frequent predator to smaller fish hooked or released.

How Depredation Impacts Fish Populations

Frequent depredation events can cause numerous problems for a fishery, so I’m going to split this up into two scenarios: Pre-catch and Post-release.

On the pre-catch side (while a fish is fighting to the surface), depredation can lead to both economic and ecological issues. Anglers lose money from tackle and often become frustrated with the predators causing these losses. This frustration sometimes leads to anglers taking action or retaliation to those predators. From a fish population standpoint, if you lose 10 fish to predators before catching your hypothetical 2-fish limit, then 12 fish are removed from the ecosystem.

On the post-catch side, predation and depredation can lead to significant increases in post-release mortality. These mortality rates are typically established through research and applied to the releases to account for a total number or percentage of “dead discards”. This portion of the catch is then removed from the quota you are allowed to harvest. The more dead discards there are, the less anglers can actually harvest to eat, which results in significant waste for the fishery.

Factors That Increase Depredation Risk

Factors that affect depredation are still being studied. There are certainly hotspots for predators, but it seems as though on any given day you can experience depredation on every fish you catch, or not once throughout the entire day. Different predators also frequent different areas. Goliath grouper likely will remain around the same wrecks and artificial reefs, while sharks migrate long distances and dolphins will follow you for miles. The interactions between humans and predators has certainly increased significantly in the past 5 years, and that is likely due to a combination of increasing predator populations and increasing number of anglers out on the water. Dealing with these interactions is an increasing challenge for anglers doing their best to keep their catch alive.

Understanding Descending

To better address the second major challenge of discard mortality, we need to know what barotrauma is and how it affects fish. Barotrauma is a pressure-related injury that reef fish experience when reeled up from deep-water, typically 50 feet or greater, but it can be shallower for some species like hogfish. The pressure change from the seafloor to the surface causes the gasses inside the fish’s body to expand, displacing organs and leaving them bloated and unable to return to depth on their own. Descending devices are one the most effective ways to help reef fish, like snapper and grouper, recover from barotrauma and survive release.

How Descending Devices Work

Descending devices basically work to reverse the effects of barotrauma. When combined with a heavy weight, they carry a fish back down to depth, causing the expanded gasses to recompress back to their natural state. This is a non-invasive way of helping a fish overcome the positive buoyancy and get back to depth on their own. The alternative is to vent a fish, which involves putting a needle into the body cavity (particularly the swim bladder) to release the excess gasses so it can swim back down on its own.

How Descending Devices Work

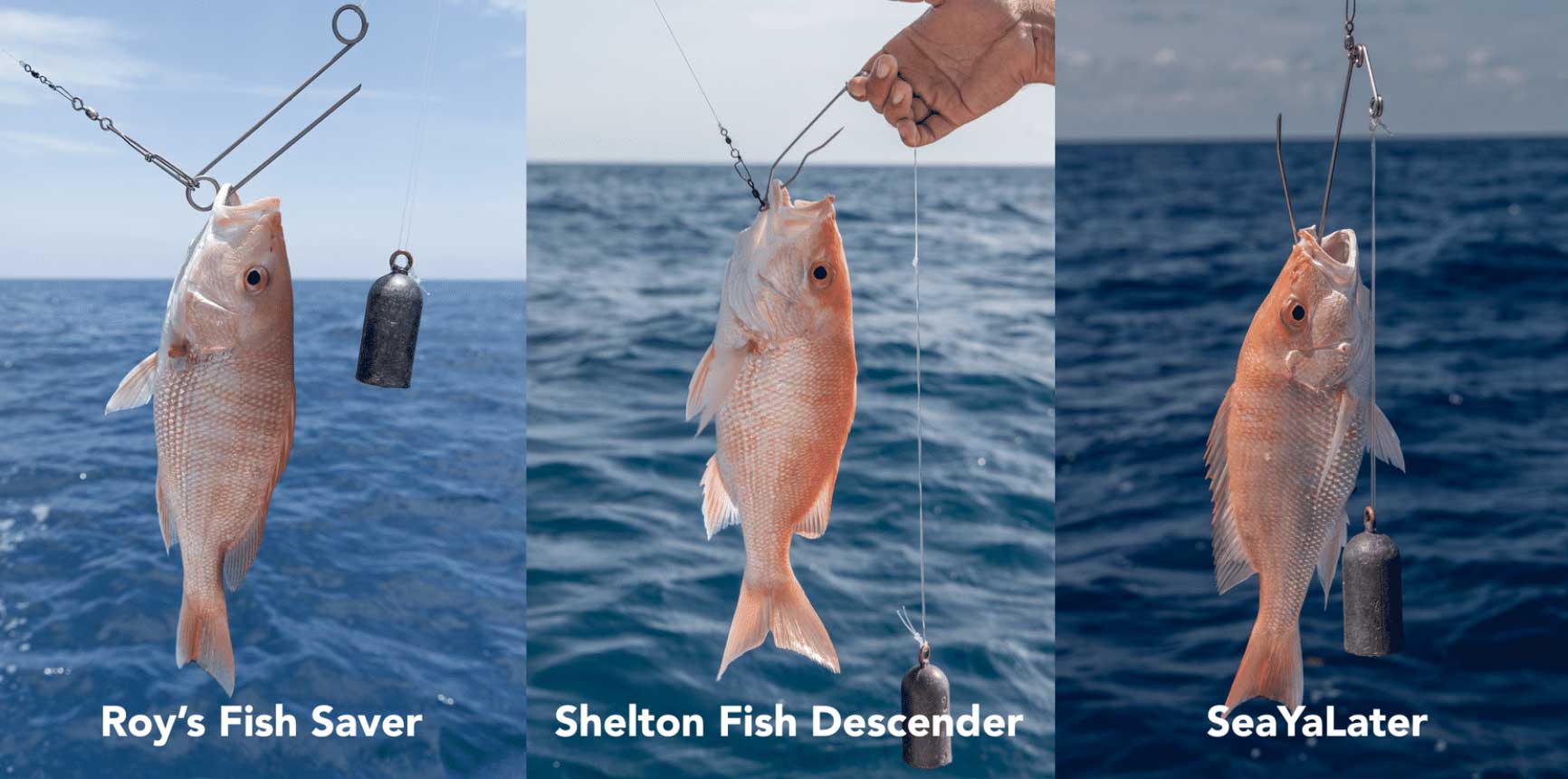

Descending devices come in a variety of styles and sizes, each with their own pros and cons. Generally, descending devices are lumped into three categories: lip grip styles, inverted hooks and weighted crates or baskets. You can even make all three of these styles at home yourself. Anglers who fish the Gulf can get two of these descending types with the weight needed to descend by taking the 15-minute Return ‘Em Right training on barotrauma, venting and descending at https://returnemright.org/about-us/gear-signup/.

Connecting Depredation and Descending

Although descending devices are typically used to help reduce discard mortality there is also a chance they could help prevent predation after release. For many years, we have heard that descending devices spoon-feed sharks, with little evidence to suggest that. In fact, the opposite could be true. We have had many anglers reach out and tell us they use descending devices specifically in the presence of sharks and dolphins to give them a better chance of getting back down to the structure or school they came from. No matter how you address these two issues, predation after release is guaranteed if you don’t treat barotrauma and let fish float off on the surface.

Protecting Fish from Predators During Release

Research also suggests that depredation on descending devices is relatively uncommon. In a recent study by Mississippi State University, out of 987 videoed descents of reef fish in the Gulf, only 3 were eaten while attached to the descending device. Additionally, we have sent a GoPro down hundreds of times and have only ever had one predator eat a fish off a descending device. This was a dolphin and we couldn’t get any fish released on the surface without the dolphins getting them. In that specific situation, I still think descending was a better method than vented and surface released fish.

The Angler’s Decision on Release

The final call whether to vent or descend fish in the presence of predators is up to the angler. Whichever method you choose, more fish are likely being consumed than we can see with our own eyes. There is no perfect solution to this issue, but I personally would rather give a fish a free ride down to the bottom where it can find protection in structure, than to rely on it swimming 150+ feet back down tired from the fight with a hole in its side past the predators.

Why These Practices Matter for Conservation

No matter how you view the changing ecosystem in fisheries, it’s important to do your best to avoid these two issues for the sake of fisheries conservation. I am saying that with the complete understanding that it’s not always possible. We’ve had days where the dolphins are taking every bait off of our hooks and other days where after catching one-two fish, we have to move spots every time because the sharks show up so quickly. With that said, don’t use “the fish is going to die or get eaten” as an excuse to not give them their best chance of surviving release.

Learn More About Responsible Release Practices

Learn more about what Return ‘Em Right is doing to reduce discard mortality and promote healthier fisheries at returnemright.org.